How Canada lost its publicly owned vaccine producing facilities

Phew! The vaccines have arrived. Notwithstanding the conflicting and confusing information regarding AstraZeneca, most Canadians are relieved to be seeing that the vaccination program, having previously experienced some hiccups, is now rolling out relatively efficiently, although unevenly and with the risk of more bumps in the road. The main hiccup came in February as the big US pharma companies, Pfizer and Moderna, announced delivery delays.

As a result of this, we had the unsavoury sight of the Liberal government going into reverse Robin Hood mode with its decision to draw on a supply of coronavirus vaccines from a global inoculation-sharing initiative, under the auspices of the World Health Organization, known as Covax. The latter pools funds from wealthier countries to help buy vaccines for themselves and, in particular, low-income nations. The scheme announced a plan to deliver more than 330 million vaccine doses in the first half of 2020. But, following the Pfizer and Moderna delays, Canada was the only member of the G7 group of rich countries that decided to become a Covax beneficiary. Meanwhile, many of the poorer countries hadn’t even started vaccinations. Back in 2015, just after being elected PM, Trudeau declared: “To this country’s friends all around the world, many of you have worried that Canada has lost its compassionate and constructive voice in the world. Well, I have a simple message for you. On behalf of 35 million Canadians: we’re back.” It didn’t take long for the man of sunny ways to put compassion on the back burner in his quest for domestic political credibility. The precariousness of the global vaccine supply points to how deeply immoral it is that the pharmaceutical industry has such sweeping life-and-death power, even in the midst of a catastrophic pandemic.

Beyond accessing the Covax supplies, the Liberals started playing catch up by looking around for a domestic vaccine producer. They found one but it wouldn’t be able to deliver until later this year. The location was in Montreal courtesy of The National Research Council-owned Royalmount facility with the Maryland-based Novavax supplying enough to produce tens of millions of doses. As the CBC reported “The agreement will help jump start Canada’s largely dormant domestic vaccine manufacturing industry.” In all the media coverage of this news, there was virtually no mention of why and how this industry had become dormant.

The fight against diphtheria

We have to go back to 1914 when diphtheria was an infectious disease that struck thousands of Canadian children each year and killed many of its victims. Many of the deaths were preventable. A life saving medication capable of treating a child with diphtheria already existed and could be purchased through Canadian pharmacies but that was of no help to the thousands of Canadian families who couldn’t afford it – a full dose of treatments cost about $80, the equivalent of several weeks’ wages for most workers. “The children of any but the wealthy are left to die of diphtheria,” observed the chief medical officer of Ontario at the time. Then along came a young medical doctor, John G. FitzGerald with a mission to find a cheap treatment for diphtheria.

Experimenting with horses in a barn behind his house, he developed diphtheria immunity in the horse’s blood from which he derived a serum to treat the disease. From this cold, crude laboratory barn, Fitzgerald was able to develop a treatment that would be distributed for free to any Canadian who needed it. As important as the diphtheria breakthrough was, more significant in the long run, was Fitzgerald’s push to ensure that free access to life saving medication should be universal, that the medicines be available to rich and poor alike. Prior to WW1, this was a notion that was radical and novel. Also important was the key role to be played by government. Rather than trusting to private delivery, Fitzgerald understood that only a public system would ensure his medication would be made available to all Canadians. To help him in his quest, Fitzgerald sought the support of the University of Toronto. The U of T granted Fitzgerald’s request for space to carry out his research by allocating a small area in the basement of the medical building. This was the beginnings of Connaught Medical Research Laboratories.Within a couple of weeks of working in the lab, Fitzgerald had prepared his first batch of the serum. He sold it to Ontario’s Board of Health for one fifth of the commercial rate. It quickly showed effectiveness in treating diphtheria, prompting a flood of orders across Canada in the weeks that followed.

Connaught – insulin, polio and more

Connaught’s mandate meant that they were not subject to commercial interests and they could ensure the medications they developed remained accessible. Most Canadian students learn in their High School History class of the Canadian “heroes,” Banting and Best who, in 1923, discovered insulin, a treatment for diabetes. What the history textbooks generally emphasise is the efforts of two scientists in making the medical breakthrough. What the books usually omit is that the discovery of insulin could have made the two men very rich, but they decided not to get rich from the patent, selling to U of T for $1. Contrast this to the drug companies with COVID vaccines! Also omitted is the fact that Connaught Labs was crucial in developing insulin and bringing it to market at cost. In the 1930s, methodological advances at Connaught updated the international standard for insulin production. Efforts at Connaught to purify heparin for human clinical trials lay the foundation for various critical surgeries including vascular surgery, organ transplants and cardiac surgery. During the First and Second World Wars, the Labs produced various antitoxins that became crucial due to increased risks of injury infection and exposure to diseases in other parts of the world, including the typhus vaccine and penicillin.

Connaught’s production technologies also enabled the mass-scale field trial of Jonas Salk‘s polio vaccine and its subsequent expansion in the 1950s. The institution played a particularly important role in restoring US public faith in the polio vaccine after a production mishap at California-based Cutter Laboratories.

The end of Connaught

The high point of public health advances in Canada came in the 1960s with the struggle of Tommy Douglas and the NDP in Saskatchewan to introduce medicare for all. The 1960s, while seeing much progress and radicalisation (including the extension of universal medicare to all of Canada), also saw some right-wing rearguard actions with the public status of Connaught Labs falling in the crosshairs. The struggle over medicare was a bitter one with the conservative medical establishment (the Canadian Medical Association) being strongly opposed to medicare. In the Connaught/U of T context, this led to serious tensions. The Connaught team, dubbed by some as “the little red schoolhouse” were lined up against the U of T’s conservative Faculty of Medicine, advocates of private medicine. Unsurprisingly, senior university officials were more closely aligned with the Faculty. They were supported by the leaders of the private drug industry in Canada who had long been bothered by Connaught’s tax-free status. There was a Connaught committee which oversaw the Labs for the U of T Board of Governors. The head of this committee in the early1970s was the president of IBM Canada so it was no surprise that he favoured selling Connaught even though the lab had paid its own way from the beginning and had even contributed funding to other research institutes. The sale of Connaught was seen as a lucrative opportunity for U of T at a time when it was faced with considerable expansion costs as baby boomers were arriving at the university in large numbers.

In 1972, Connaught was sold to the Canada Development Corporation (CDC), a federally-owned corporation charged with developing and maintaining Canadian-controlled companies in the private sector through a mixture of public and private investment. The sale continued to stir controversy in the following years as the Labs increased prices on its products and came under allegations of mismanagement and deteriorated manufacturing standards. In 1986, the lab was transferred to private ownership with the CDC being dismantled as part of the Mulroney government’s program of privatization – a privatization pleasing to pharma companies that had never liked competing with Connaught.

After going through a series of acquisitions and mergers, ownership ended up with the French pharmaceutical multinational, Sanofi. The old Connaught horse farm remains on the site of Sanofi’s sprawling biotech operation in Toronto, but it is essentially a branch plant in the same way that General Motors Oshawa is a branch plant of GM in Detroit.

New lease of life for Connaught or a sweet deal for Big Pharma?

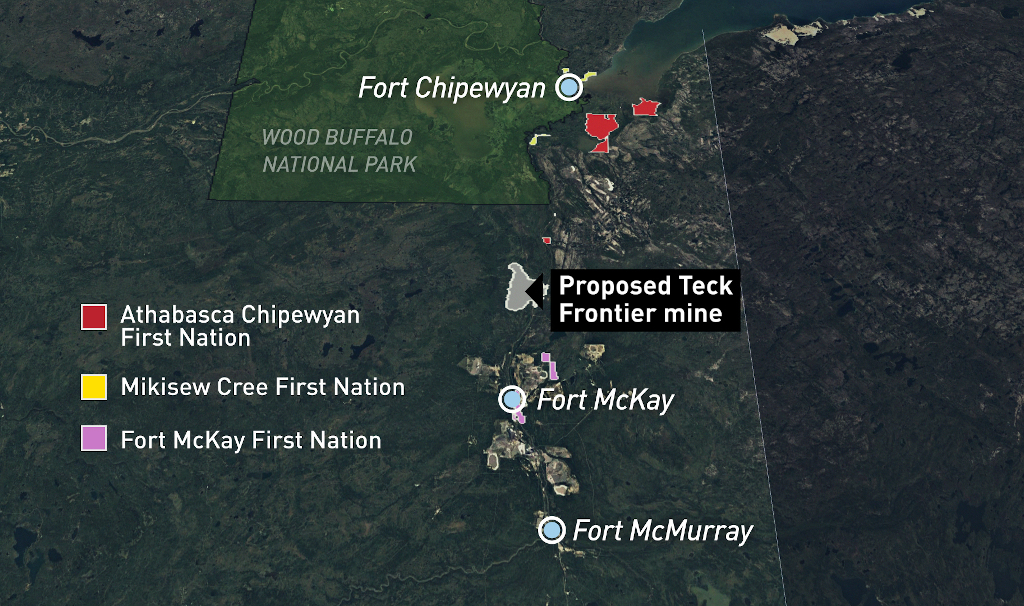

While Sanofi is not a major player in the global COVID vaccine market, its plan was to produce vaccines primarily at its US and European plants, putting Canada at a “disadvantage,” as Trudeau said. He acknowledged that Sanofi would likely deliver vaccines first to the countries where they’re produced but “shortly afterwards” would start honouring contracts “they signed with other countries, including Canada.” So, while the privatized Connaught plant remains operational, Canada no longer controls what goes on there.

In early April, came another twist involving Sanofi or what used to be Connaught labs. The federal and provincial governments announced a plan to build a $1bn new production facility at the Sanofi/Connaught site. The feds will invest $415 million, Ontario’s government will contribute $55 million, and Sanofi will come up with $455 million, less than half. The facility will become operational in around five years time. In other words, this isn’t a plan to deal with the present vaccine supply problems but to have something in place for the next pandemic.

Is this a case of forward thinking from Ottawa or an attempt to answer political criticisms that the government was unprepared for the COVID 19 outbreak and was also over reliant on foreign multinationals for vaccines? Doug Ford was as pleased as punch about the announcement. “We are now never going to have to rely on any country, any leader, we will be self-sufficient,” he said. But even domestic production is no guarantee of supply, as Pfizer’s Belgium plant is exporting to the UK over supplying Belgium and the rest of the EU. As socialists and internationalists, the key point is not where drugs are made but that they are effective, cheap, shared globally and arrive in a timely fashion. When a global crisis like COVID emerges, it requires a global solution – co-operation, planning and pooling of resources. Under capitalism, this isn’t possible.

Linda McQuaig, Toronto Star columnist, commented on the public-private deal involving Sanofi, “That is not a solution. On the contrary, it’s a reckless use of a lot of public money.” She went on to say that it was unclear what strings are attached – if any – to the half a billion dollars of public money since the negotiations with Sanofi over a contract are ongoing. McQuaig correctly comments, “surely it would have been better to postpone announcing the $415 million until after Sanofi had agreed to the government’s terms about priority access for Canadians. Without that nailed down, we can just keep our fingers crossed that Sanofi will come through for us in the future.”

The pandemic has only increased the clout of Big Pharma – within Canada and without. “That increased clout may explain why Justin Trudeau sided with Big Pharma – risking his image as a “progressive” – in opposing a World Trade Organization resolution overriding drug companies’ patent rights so poor countries can access COVID vaccines.”

And in Quebec …. the Armand-Frappier Institute

Armand Frappier was a pioneering Québec researcher in microbiology and preventive medicine. In 1938 he founded Institut de microbiologie et d’hygiène de Montréal (IAF), the first French-Canadian medical research centre, which was dedicated to research, training, and the manufacture of biologics and was affiliated to the Université du Québec. One of his inspirations was Connaught Labs in Toronto. Epidemiology and the fight against tuberculosis were priorities for many years, but rapid advances in microbiology and immunology gave the new Institute opportunities to grow and helped it achieve an international reputation. During the war, the Institute’s researchers proved their scientific and entrepreneurial skills. There was a major need for blood derivatives to treat wounded soldiers, so the Institute quickly set up labs able to freeze dry the serums and gamma globulin preparations delivered to the Red Cross for distribution worldwide. It also produced diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and antitoxins for many years. Like Connaught, the Institute was heavily involved in production of the Salk polio vaccine in the 1950s.

While Connaught Labs never required government subsidies to survive, IAF’s finances were on shakier grounds in the 1980s. With the struggling economy of the time and Québec’s funding cuts, the Institute’s budget was quickly eroded. In this period, commercial operations became less and less profitable due to marketing errors, the sale of products below cost, and increasing competition in the field of vaccines. This culminated in the dismemberment and privatization of IAF in 1989. In its 53 years of existence, IAF was a resounding success. Unfortunately, nothing remains to show of that success.

Even without Connaught or IAF, we could be doing more to wrest control from the all-powerful pharma industry. Ottawa could, for instance, legally override the patent rights of drug companies, allowing Canadian generics to produce the vaccines. But Trudeau won’t do this, as he is fearful of angering drug companies by infringing on their monopolies.

For a public health system in a socialist planned economy

The whole management of the COVID crisis – from the insufficient stockpiling of PPE (masks, etc.), to the criminal incompetence around long-term care homes, to the vaccine roll out, to the stop go series of lockdowns/relaxations – has shown the limits of capitalism to work for the public good. Doug Ford has maintained that his government’s decision-making has been based on achieving “a happy balance” between the needs of “the economy” and the interests of public health. The profits of the pharma companies ($4bn for Pfizer on $15bn sales of their vaccine) show whose interests are being looked after first. The fact that Canada is the only advanced country (apart from the US) that has no national pharmacare program is further evidence of the influence of Big Pharma and how governments have been in thrall to them. The time has come to take them down. Not just that – the time has come to restore the traditions of Connaught Labs and the Armand Frappier Institute. For a full service, public health system in a socialist planned economy.