The path to remote teaching starts with cautious curiosity, goes through enraging frustration and ends with a tired, tenacious and uninspired slog.

The Cautious Curiosity

COVID-19 has shutdown physical K-12 classrooms across Canada. In BC spring break ended on March 30, not with a return to school but with teachers logging onto their computers to start rolling out remote learning. I returned to my job as a high school teacher, ready to try out remote learning but also wrestling with a million questions of how to do it in any meaningful way.

Remote learning in the times of COVID-19 is not to be confused with Distance Learning in “normal” times. Distance Learning in BC is optional, can allow for some in-person meetings, and is undertaken by families and students who can support learning at home. Meanwhile, the current remote learning is imposing online learning on all teachers, students and parents in a matter of weeks with very little preparation regardless of their home situations.

Remote learning raises all sorts of issues around equity and access. Never mind whether the student has the intellectual ability to do assigned work. Do students have access to internet? Do they have access to a device on which they can do schoolwork? Are students available during the day or are they providing child care for younger siblings? Are students out earning money for their struggling families? Are their homes suitable learning environments? Are my students with mental health struggles still able to access support given that the free counseling schools provide is now over the phone?

All these questions have been buzzing around my head as I adapt my teaching to the new circumstances. Are teachers responsible to resolve any of these issues? No, teachers are not messiahs, nor should they be martyrs to their students. These issues existed even in normal times, but the COVID-19 crisis has definitely made them worse.

However, teaching curriculum is not like following a recipe that works every time. Effective teaching is providing a bridge from students’ present conditions and levels of understanding to the concepts and the content found in the curriculum. Teach too low or too high above students’ conditions and levels of understanding and you lose the class, and each class has students with varying conditions, levels of understanding and ability.

COVID-19 has not created these inequalities and inequities in our society, but it has made them starker.

I have students who are sitting at home thrilled that school is now remote. I have students that are bored out of their minds, missing their friends. But I also have a grade 9 student who is now caring for her immune-compromised mother, who cannot leave her home. I have grade 10s working full time at gas stations and grocery stores, trying to support their families. I can’t teach as I did before without torpedoing these students.

The Enraging Frustration

School Districts generally did their best to provide students in need with school computers. Our administrators told us that “we are in this together.” Our administrators told us how to log on… and then left us to our own devices. We spun like weathervanes in a tornado of contradictory instructions. “Set up your online platforms! Don’t set up your online platforms, let the three tech workers do it! The tech workers are swamped, set up your online platforms immediately!” I spent two weeks on the phone and on the computer figuring out an online platform with a colleague before turning around and trying to explain it all in writing to my students.

But the new online platforms were just the tip of the iceberg. I’ve spent tortuous hours in front of my laptop trying to unlearn how to do my job well – engaging and not just drawn from a turgid textbook. I’ve had to learn how to deliver boiler-plate lessons that have the impossible goal of being engaging, varied, worthwhile and mindful of different learning abilities, while also being completely clear without any verbal instructions on a new software platform. Impossible! I spent hours for weeks providing tech support to my students just to get them online.

My school has continued to have bi-weekly staff meetings online. We’ve been told that our homes are now District workplaces and that we should make sure they are compliant with health and safety regulations. Isn’t that the employer’s responsibility?! Ending each day with a sore back after perching for eight hours on a dining room chair, I could definitely use a proper ergonomic chair and desk. Hell, I could buy one. But where would I stick it in my tiny one-bedroom apartment?

Initially the BC Ministry of Education said that all students would pass their classes. Then a few weeks into remote teaching we were told that all work and marks would count. Since last week, my District requires students to do work online if they wish to improve their pre-spring break marks. Teachers are left to try to dampen the inequality in this situation. Publicly our society is banging pots to thank “front line workers” but some of those workers are our students and Districts are setting these celebrated “front line workers” up to have very different outcomes from their peers.

The Slog

A month into remote teaching, I am delivering 20 percent of the usual content, but working the same hours as before, without the generally pleasant interactions with students and colleagues. I can’t use facial or physical cues from students to help me teach. I can’t discuss the work or do a quick homework check. For every assignment, I have to read 30 to 100 pages per class but then can’t discuss it with the class in order to synthesize the day’s information unless I plan to write a book each day. A regular Social Studies homework check would take two minutes and result in a 20-minute conversation. Online, the same work takes at least an hour of focused work. Remote learning is extremely one-on-one and extremely time intensive.

Given students’ unstable routines and schedules, we can’t expect many of our students to be online in order to conference with us. We are legally required to call up those who don’t show up online for a week. So, Friday afternoons I spend a couple of hours phoning families about their child’s whereabouts.

The rush of emails asking for help has slowed. I no longer turn on my computer to find 32 emails on Monday morning. The rush has turned into a trickle. Does it mean that we’re all getting better at this remote learning thing? On good days, I think so. On bad days I think we, teacher and students, are just learning to give up a little bit more to make it through the week.

I can’t wait for school to re-open but am also terrified of reopening because I don’t have faith that it’ll be based on sufficient testing data but rather on economic imperatives.

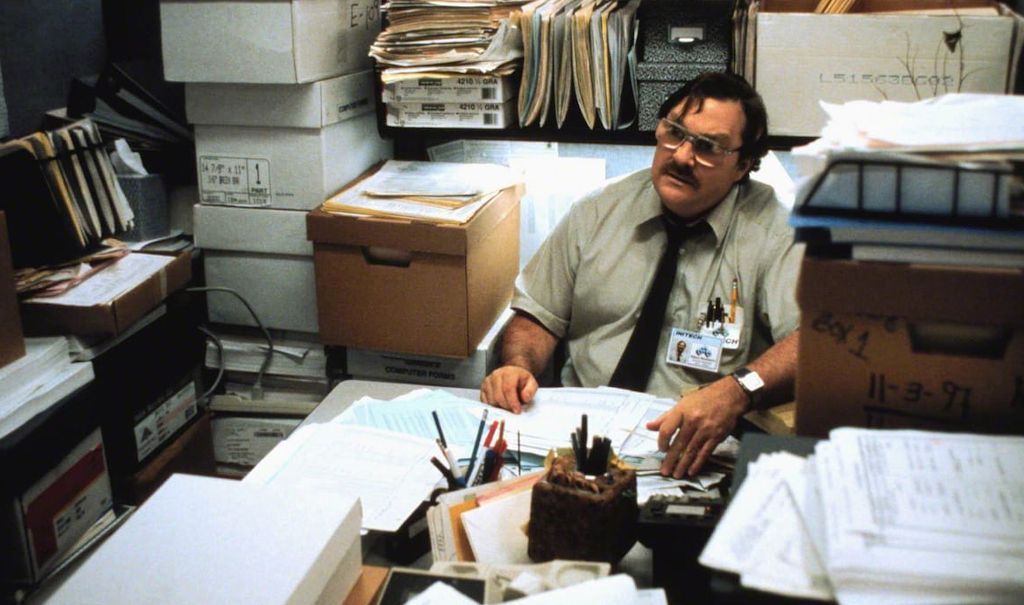

In sum, all the fun, social aspects have been sucked out of the job or are extremely hard to create. The best day of the week is now Monday, as I get to bring some creativity into what my students will learn that week. The rest of the week is paperwork.

This crisis is a giant reminder of the importance of well-funded, face-to-face public education!