Arne Johansson is a member of Rättvisepartiet Socialisterna (ISA in Sweden).

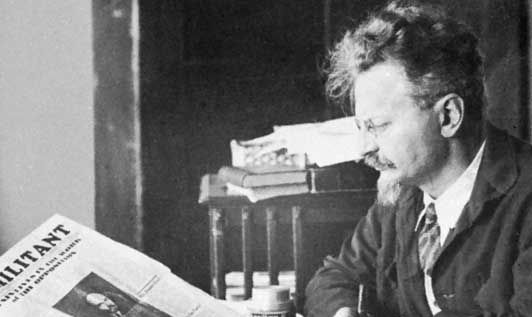

Pierre Broué takes us on a historic journey that begins with Lev “Lyova” Davidovich Bronstein’s birth on a Ukrainian farm in 1879, the early struggle of his teenage years to understand Marxism and his enthusiastic attempts to organise the Southern Russian Workers’ Union during the revolutionary awakening of the 1890s. The latter soon led to imprisonment and deportation to Siberia, Trotsky’s debut as a writer and his first flight into exile.

The biography vividly describes the young Trotsky’s first meetings with Lenin and Iskra’s editorial staff in London as well as his spectacular role at the head of the first Soviet (workers’ council) in St. Petersburg during the revolutionary dress rehearsal of 1905. It was an experience that strengthened him in his formulation of the theory of the permanent revolution. Based on an analysis of the “uneven and combined development of capitalism,” Trotsky predicted how the revolution could win in Russia, as capitalism’s weakest link, as a prelude and impetus to revolution in the more developed countries.

Lenin and Trotsky found it difficult to come to agreement for a long period of time. Long before Trotsky, Lenin had understood the crucial importance of gathering the most conscious socialists in a disciplined party of revolutionary cadres, but bent the stick a little too far in his formulation that socialist consciousness must be brought to the working class from the outside while keeping the question of the tasks of the revolution open.

The February Revolution of 1917 and, above all, Lenin’s “April Theses”, which argued, in opposition to most of the Old Bolsheviks, that the workers must seize power with the support of the poor peasants under the slogan of “All Power to the Soviets” created new conditions for Trotsky’s entry into the Bolshevik Party in the summer of 1917.

This laid the foundation for a close relationship through the crisis-filled ups and downs of the October Revolution and the ensuing civil war.

The October Revolution was not, as the propaganda of the right claims, a minority-based “coup” in favour of a sinister “doctrine” of proletarian dictatorship, based on “war communism” and “Red Terror” with bans on parties and factions.

“By tens of thousands the working-people poured out … Red Petrograd was in danger! … toward the Moskovsky Gate, men, women and children, with rifles, picks, spades, rolls of wire, cartridge-belts over their working clothes…Such an immense, spontaneous outpouring of a city never was seen”, according to the American journalist, John Reed, in Ten Days That Shook the World.

That the conditions for revolution were overripe was also shown by the increasing number of mass desertions from the front after three years of a devastating world war and by a powerful movement of land occupations by the peasants of the vast country. The uprising had overwhelming support because the never-elected Provisional Government betrayed all the demands of the workers, soldiers and peasants for bread, land and an end to Russia’s participation in the World War.

In the elections to the second All-Russian Soviet Congress that took power, 20 million workers, soldiers and peasants took part giving a majority to the Bolsheviks who were also supported by the left-wing of the Socialist Revolutionaries.

Broué also quotes Victor Serge, a former anarchist, on the real situation immediately after power was taken, where the support of the Soviet Congress and its decrees on peace and land for the peasants were enough to spontaneously spread the revolution like wildfire across the vast country:

“In Russia and abroad, only the dictatorship of Lenin and Trotsky was spoken of. That was completely wrong. The Central Committee, the Soviets, and the local committees freely and discussed all matters, and violent disagreements often arose. All decisions were submitted to party meetings, soviets, congresses and leading bodies. That is how a lively democracy worked – with too much debate at times – in which, moreover, the socialist opponents were not denied any rights.“

Broué’s description of the early Soviet democratic power and its tolerance of the counter-revolution is, unfortunately, extremely brief, which is all the more surprising as this is something that has been concealed by both bourgeois and Stalinist historians.

One must turn to Victor Serge’s brilliant Year One of the Russian Revolution to find a detailed account of the White Terror, which was first implemented by the White officers who had taken refuge in the Kremlin. Despite the massacres they committed, they were released without punishment. The officers were even allowed to keep their handguns!

Broué, who devotes much space to the disagreements within the leadership of the Bolshevik Party during the peace negotiations with Germany led by Trotsky in Brest-Litovsk, unfortunately completely ignores the first horrific bloodbath after the October Revolution that was taking place at the same time. A battalion of Swedish volunteers and Swedish officers with senior positions in Mannerheim’s White Army would be the first to, together with the Finnish Civil Guard and German troops, implement mass terror against the defeated workers in the Finnish Civil War.

Victor Serge claims that about 100,000 workers, a quarter of the entire Finnish working class, were either killed or put in concentration camps.

Imperialism’s invasion of Russia in the summer of 1918 seemed to break the revolution by pushing it back to the Grand Duchy of Moscow. This is how the White Terror created its Red counterpart.

Trotsky, who turned down Lenin’s offer to become the head of government, would, after the interlude in Brest-Litovsk, be the one to build up the Red Army.

From his famous armoured train, he organised the first Red Guards into an army which, at an awfully high price, would emerge victorious after a three-year long bloodbath, without “white gloves on a polished floor” in the struggle against the counter-revolutionary generals who were supported by 21 foreign armies.

The repression, which was introduced gradually, was aimed at defending Revolutionary Russia from the armies and political assassinations of the counter-revolution and simply surviving until the revolution spread to Germany and other developed countries. It was also aimed at defending “war communism” – the forced requisitions of food to supply an army that would eventually become five million strong and a starving urban population. This was at a time when the front was shifting back and forward, the working class was scattered and largely forced to abandon the cities, the internal life of the Soviets had ceased, industries had been laid to waste, money had become useless and the best revolutionaries had died like flies at the front.

In fact, according to Broué, Trotsky was the first to raise the question of replacing the forced requisitions of war communism with a tax-in-kind and temporary concessions to the market. When he did not find support for this, he instead suggested that the army should, instead of being demobilised to unemployment towards the end of the civil war, be used as military labour brigades in the work of reconstruction. However, his proposal to order the unions to take the lead in the economy and plan the reconstruction and industrial development, which he considered a necessity to compensate for the lack of an economic centre, led to a strong backlash. The Bolshevik Party initiated a public debate with votes throughout the country. Trotsky would later admit that Lenin, who clearly won the debate at the turn of the year 1920/1921, was right that the unions must be independent of the state which “is partly not a workers ‘state, but rather a workers’ and peasants’ state, and partly a workers’ state with bureaucratic distortions.”

The Belgian Trotskyist, Ernest Mandel, in his review of Broué’s book in 1988, was sharply critical of the fact that he did not admonish Lenin and Trotsky for not beginning to tear up the ban on parties and factions and taking steps to re-establishing Soviet democracy after the end of the Civil War in 1921. Instead it was reinforced.

However, most indications are that even then this would have created unpredictable consequences in a situation where the working class was enormously weakened and scattered because of the civil war and when no local Soviets could function normally before the economy and social life had first recovered.

As Trotsky would later explain in the pamphlet, Bolshevism and Stalinism, the ban on other parties did not follow any Bolshevik “theory” but rather the necessity of defending the revolution in a devastated and destitute country, surrounded by enemies everywhere.

“For the Bolsheviks it was clear from the beginning that this measure, later completed by the prohibition of factions inside the governing party itself, signalised a tremendous danger.” And further: “If the revolution had triumphed, even if only in Germany, the need of prohibiting the other Soviet parties would have immediately fallen away. It is absolutely indisputable that the domination of a single party served as the juridical point of departure for the Stalinist totalitarian regime. The reason for this development lies neither in Bolshevism nor in the prohibition of other parties as a temporary war measure, but in the number of defeats of the proletariat in Europe and Asia.”

It was clear in 1921 that the revolution in the West would be delayed and the Russian revolution risked being isolated for a longer period than expected. Still, it was the unfinished revolutions that toppled the empires of Central Europe and inspired by the Russian revolution which led to the victory the Red Army, the formation of the Soviets in Sofia, Budapest, Vienna and Berlin, revolutionary convulsions even among Allied troops and a definitive end to the carnage of the First World War.

Lenin and Trotsky, who quickly repaired their relationship after the debate on the Russian unions, soon after launched a joint battle at the Third Congress of the Comintern against the ultra-left line which, through pure provocations, tried to spark a new German revolution in March 1921. That was the background to Lenin’s book, Left-Wing” Communism: an Infantile Disorder, and the conclusions of Trotsky’s in-depth analysis of tactics in relation to social democracy in the classic, Report on the World Economic Crisis and the New Tasks of the Communist International.

They argued that the Communists must apply a united front policy in order to win over a majority of the working class to transitional slogans like the struggle for a “workers’ government”.

Not only Trotsky but also Lenin from 1922 and towards the end of his life became increasingly alarmed at how the Russian Communists had become prisoners in “the vast and swollen bureaucratic machinery.” “Who is leading whom?” asked Lenin over and over again. On several issues, such as the proposed abolition of the monopoly on foreign trade and Stalin’s brutal repression of Georgia’s independence behind the backs of the Central Committee, he sought a bloc with Trotsky, backing Trotsky’s idea of strengthened state planning of the economy.

“I declare war to the death on Great Russian chauvinism”, explained Lenin in a note to the Politburo.

Broué proves without a doubt Trotsky’s claim that Lenin’s addition to his testament that Stalin should be removed as General Secretary was not a temporary reaction, but that he, shortly before his death, really did plan to wage a public battle on this issue.

Afterwards in My Life from 1928, Trotsky was convinced that they could have won an open battle in 1922–23 against the faction of what he called “national socialist officials, of usurpers of the apparatus, of the unlawful heirs of October, of the epigones of Bolshevism”.

Broué‘s biography is a head above Isaac Deutscher’s, especially when it comes to the various turns in Trotsky’s long struggle against Stalinism – from the Left Opposition in 1923–25 to the Joint Opposition with Zinoviev and Kamenev in 1925–1928 and the tentative attempts to create a new bloc against Stalin at the start of the terror of the early 1930s.

The possibility that Trotsky would take over Lenin’s role in the leadership of the Soviet Union initially led old opponents such as Zinoviev and Kamenev to align themselves with Stalin and form a blocking triumvirate with him.

Although the contentious issues, with the exception of the Georgian question and the rapid bureaucratisation, were still relatively vague and Lenin’s state of health unclear, Deutscher and other critics – with the benefit of hindsight – sharply criticised Trotsky’s choice to keep a low profile and bide his time at the 12th Party Congress in the spring of 1923, as well as to refrain from publicly publishing Lenin’s Testament. In addition, following an agreement with Kamenev, Trotsky was allowed to present the economic report to Congress on the issue he currently considered most important, though not yet as controversial, and which would soon become a central part of the Left program of the Opposition. By arguing for a planned strengthening of industry and thus the working class that could support the future Soviet democracy, Trotsky hoped to gain more time for the revolution by matching the growth of private capital with increased productivity and lower prices for industrial goods.

He presumably also wanted to wait for the new possibility of a German Revolution after French and Belgian troops had occupied the Ruhr area in January 1923 and provoked a severe crisis with runaway inflation.

But the massively strengthened German Communist Party, in the presence of the Comintern’s advisers, missed a crystal-clear opportunity to seize power in October 1923. This was the straw that caused everything to explode and necessitated an open battle. “passive obedience, mechanical levelling by the authorities, suppression of personality, servility, careerism – should all be kicked out of the party!” wrote Trotsky in an appeal to the youth, well aware that he would probably not get the majority of the leading cadres to side with him.

The loose tendency that came to be known as the “1923 Opposition” began with Trotsky’s document, The New Course. Relatively cautiously and without yet demanding the abolition of the party monopoly, he nevertheless spoke clearly about the “excessive increase of functionaries in the party” who had created new social strata with their own interests and a “bureaucratic faction” at the top who had a “corporate class spirit.” Something that must ultimately be broken with the advance of the world revolution and economic development. Even more outrage was evoked with his book, The Lessons of October, which compared the experiences of the October Revolution in Russia in 1917 and with that in Germany in 1923.

The support he received after Lenin’s death led to a furious campaign to isolate Trotsky by the Triumvirate (Stalin, Zinoviev and Kamenev). They did everything to bring up Trotsky’s differences of opinion with Lenin before 1917, at the Brest-Litovsk peace talks and the trade union debate, his alleged “underestimation of the peasants” and so on.

At the same time, a so-called “Leninist levy” was introduced to strengthen the leadership’s grip by recruiting 200,000 new and inexperienced members of the party, while students and workers who supported the opposition were expelled, demoted or relocated. The Comintern was “bolshevised” further under Zinoviev’s leadership with a purge of leaders in, for example, the Polish, German and French parties.

For Trotsky, at least in the short term, it was not about a struggle for power, but about educating and schooling a new generation. “An overwhelming majority of the working class are Trotskyists, as evidenced by the large turnout wherever Trotsky appears. But all this leads to a 100 percent majority for the Central Committee at the Congress,” as the French communist, Boris Souvarine, described the situation in June 1924.

At the same time, Trotsky’s demotion and resignation as war commissar paradoxically gave him space to become a brilliant commentator on everything from a critique of “proletarian culture” to articles on the problems of families, women, youth and everyday life, and on science.

But, as Broué shows, even Zinoviev and Kamenev soon began to worry that the NEP, combined with the delay of the world revolution, could lead to a reintroduction of capitalism based on the kulaks, the 3–4 percent of the most affluent peasants.

Like it was for Trotsky, Stalin’s new speech on “socialism in one country” was for Zinoviev and Kamenev a completely un-Marxist slogan, which the ruling bureaucracy tried to use in a time of fatigue and a sense of isolation.

Zinoviev and Kamenev acknowledged the role they played in tarnishing “Trotskyism.” This enabled the declaration of a tendency by the “Joint Opposition”. This declaration, which soon caused the espionage and faction accusations to flourish, was supported by exactly half of the surviving Central Committee members from 1918–1920. The political criticism was directed at the bureaucratic deformation and at the Central Committee’s policy of lowering real wages, slowing industrialisation and concessions to the rich peasants of Soviet Russia. They also warned of opportunism in foreign policy, such as support for the Anglo-Russian Committee, despite the betrayal of the 1926 General Strike by the English trade union leadership.

According to Broué’s estimates, the Joint Opposition was supported at the 15th Party Congress by about 8,000 party members, compared to the 20,000 who actively supported the party leadership, out of a grey mass of 750,000 members.

After being ground down by threats, purges and their own concessions on factional work, the struggle flared up again in 1927 as a result of the Stalinists’ disastrous advice to the Communists in the Chinese Revolution. Furthermore, the opposition insisted that Russian industrialisation must be accelerated and that small and medium-sized farmers be supported through voluntary collective farming and agricultural machinery, paid for with a tax on the kulaks and favourable loan rates.

Broué depicts the dramatic turns of secret meetings, “smytchki”, and public demonstrations that preceded the expulsion of Zinoviev and Trotsky on 14 November 1927, exactly ten years after the October Revolution. He further describes the split of the Joint Opposition and the pandemonium following Trotsky’s deportation to Alma Ata on 16 January, when a gathering of 10,000 supporters at the railway station caused the GPU security service to postpone the departure for 48 hours.

The capitulation of Kamenev and Zinoviev meant a severe setback, but the Left Opposition led by Trotsky would now dominate the opposition with a clearer message.

An impressive contact and courier business was also developed among exiled Communists, relations were maintained with 108 “colonies” populated by, amongst others, around 8,000 deportees to Siberia and Central Asia in 1928.

In just seven months between April and October 1928, with the help of his then 22-year-old son, Leon “Lyova” Sedov, who would become his main collaborator, Trotsky sent 800 letters while receiving 1,000 letters and 550 telegrams from his followers in the new “Bolshevik-Leninist faction”, as well as the publication of an opposition bulletin. Important works from this time are Trotsky’s The Third International after Lenin including his criticism of the proposed program put to the 6th Congress of the Comintern, which the American, James P. Cannon, and the Canadian, Maurice Spector, came across and which led to the formation of the Left Opposition in the United States, Canada and after that in other countries.

The opposition also made such significant progress among young people and workers that Stalin soon decided to deport Trotsky abroad, which took him to the island of Prinkipo (Büyükada) in Turkey in early 1929.

At the same time, there was a deep supply crisis and a hoarding campaign among the peasants, which would drive Stalin’s centre to a break with Bukharin’s right-wing.

This ushered in the forced collectivisation of the 1930s – “down to the last chicken” – and industrial five-year plans to build up heavy industry. This dramatic patchwork of ideas almost resembled an, as equally terrible as extreme, caricature of the Left Opposition’s economic program. Internationally, it led to a senseless definition of social democracy as social fascists.

At the same time, it contributed to a capitulation from some of the opposition who, like Radek and Preobrazhensky, saw the right-wing of Bukharin, Rykov and Tomsky as a greater threat than Stalin.

Broué describes the theoretical correspondence between Rakovsky and Trotsky on the parallels to the “thermidor” (the month of the French Revolution when the right-wing gained control), which Trotsky would develop in the mid-1930s into a more complete analysis of the nature of the Stalinist reaction in his most important masterpiece on the character of Stalinism, The Revolution Betrayed.

Just as the reaction of the French thermidor epoch between Robespierre and Napoleon had taken place without the restoration of the old landowner empire, the thermidor of the Stalinist regime, which he believed began in 1924, had given power to a bureaucratic apparatus that regarded the state as its private property – without having changed the economic and social basis of the deformed workers’ state. The restoration of workers’ democracy would require a new political revolution, though not a social one, as well as the international spread of the revolution.

Broué‘s most striking “new” material compared to what Trotsky himself was able to publish for security reasons and Deutscher had access to is about the relations that his son, Leon Sedov, had established with the opposition within the Soviet Union. They had, despite extreme repression, been reactivated in 1931 as a consequence of the terrible consequences of Stalin’s policies – which included “absolute poverty on a mass scale” among the workers and the death of seven million peasants, after they first cut the throats of their cattle.

Once again, it was Christian Rakovsky, one of Trotsky’s most loyal supporters alongside Sedov, who first documented the grotesque social catastrophe behind the impressive growth figures soon to be announced.

A large proportion of the “unrepentant” deportees, who in one year increased in number from 700 to 7,000 in November 1930, were still, and increasingly, active.

According to a report, thousands of new workers who had not previously belonged to the opposition joined, since every convulsion created “new Trotskyists or half-Trotskyists” including even former Stalinists like the Sten-Lominadze secret faction led by the former Young Communist.

According to Broué, in 1932, Zinoviev also described his break with Trotsky and the Left Opposition in 1927 as the worst mistake of his life, worse than the opposition to Lenin in October 1917. It was at a time when Sedov reported that exhaustion had begun to escalate into desperate resistance – more strikes, workers’ uprisings in Ivanovo-Voznesensk and minor civil wars in the Caucasus and Kuban.

A key role in the regrouping that Broué describes was played by Smirnov and other “Trotskyist ex-capitulators”, who, according to Sedov, regarded his previous capitulation as purely tactical, and who was in contact both with former opposition figures such as Preobrazhensky and new secret opposition groups from several quarters. There was talk of a new anti-Stalinist “bloc” that has been formed in June 1932 with both the Trotskyist ex-capitulators, a group of former members of the Workers’ Opposition, such as Shlyapnikov, and the “Zinovietes”, who according to Broué at the time saw it as possible to oust Stalin as General Secretary. Even “right-wingers”, such as the Ryutin-Slepkov group, who had refused to capitulate with Bukharin and broadened their program with demands for workers’ democracy, sought cooperation.

According to Trotsky, however, it was mostly an exchange of information, with a mutual right to criticise, and not a merger.

Although the GPU quickly revealed Ryutyn-Slepkov’s contacts with Zinoviev and Kamenev, who were again expelled and deported, and sentenced Smirnov to ten years in prison, no information was leaked about the “bloc” and Sedov’s channels until a new wave of arrests after the murder of the Leningrad party leader, Kirov, in 1934.

According to Broué, the exposure of the 1932 bloc became the main reason for the first Moscow Trial against 16 opposition figures, in which Zinoviev and Kamenev were sentenced to death as “morally complicit in the murder of Kirov” without it even being claimed that they had anything to do with it.

In Broué‘s view, the Moscow Trials – rather than meaningless and cold-blooded crimes – should be seen as Stalin’s desperate attempt to crush a threatening opposition through the most brutal political methods.

Broué’s book also shows how Trotsky, during his exile and flight from Turkey to France, Norway and finally Mexico, quickly challenged the Stalinists in international politics as well. From the opportunistic mistakes in Germany in 1923, in the English General Strike of 1926 and in China with the culmination of the revolution of 1927–28 to their catastrophic refusal to seek a united front with the Social Democrats against Hitler in Germany and their new opportunism in which the Spanish Revolution was sold out for a popular front policy aimed at vain attempts to achieve an alliance with England and France against Hitler’s Germany.

“It is probably Trotsky’s analyses of Nazism and the world situation that arose after its victory in Germany that have given him a prophetic reputation”, writes Broué. That “the most powerful proletariat of Europe, measured by its place in production, its social weight, and the strength of its organizations, has manifested no resistance since Hitler’s coming to power“, was, for Trotsky, Stalinism’s equivalent to the betrayal of social democracy at the beginning of the First World War.

To an even greater extent than the previous defeats in Germany in 1923 and China in 1927 and then later in Spain in 1937, the defeat in Germany in 1933 meant a severe moral setback even for the anti-Stalinist opposition and the self-consciousness of the working class.

Paradoxically, the bureaucracy that was ultimately responsible for the Moscow Trials that marked the beginning of its one-sided civil war against the entire revolutionary generation that had carried out the October Revolution was strengthened.

The fact that no lessons were learned from the German catastrophe became for Trotsky the definitive proof of the death of the Comintern and the need to build a new, fourth international.

Broué’s biography also allows us to follow a lot of the frantic and tactical efforts to be able to turn the small and relatively isolated Trotskyist groups towards the working class with a maintained firmness in principles but flexibility in tactics.

Like with Zimmerwald, the goal was that, enriched by the program of the first four congresses of the Comintern and the experiences of the Left Opposition, Trotsky could call for a new international capable of guiding the revolutions that would follow World War II that he was convinced would follow Hitler’s victory. It is certain that many occasions have been missed since then, but that the task is basically the same.

As Lenin repeatedly pointed out, the first revolutionary breakthrough in an underdeveloped country like Russia was “easier”, but building socialism more difficult, even impossible if isolated in the long run, while the task of achieving a breakthrough is “more difficult” in developed countries, but to then build socialism is “easier.” And as soon as such a breakthrough came, other examples would outshine the traumatic history of the Russian Revolution.

Our ways of understanding and learning from the experiences of revolutionary Marxism must be based on a dialectical method and the realisation that today we have a completely different historical situation, where for example the term “dictatorship of the proletariat” has been tainted by Stalinism and is no longer viable after 90 years of bourgeois parliamentary democracy – which itself only became a reality as a consequence of the Russian and German revolutions. Yet the task remains to break the power of finance capitalism, which is once again restricting and pushing back all democratic rights, dictating the slaughter of the welfare state and threatening us with growing environmental disasters. In several countries, revolution is back on the agenda.

What we can still be inspired by today is the example of participatory Soviet democracy from the early days of the October Revolution, which urged workers everywhere to rise up against their bloodthirsty capitalist governments, when there was no democracy or social welfare anywhere.

We can, in the words of Rosa Luxemburg just before she was murdered, and although we share her displeasure with the violence of the Russian Civil War and do not want to see this as an example for the future, say:

“Whatever a party can, at a historic hour, provide in the way of courage, drive in action, revolutionary far-sightedness, and logic, Lenin, Trotsky, and their comrades gave in full measure. All the revolutionary honour and the capacity for action that were lacking in Social Democracy in the West, were to be found among the Bolsheviks. Their October insurrection not only in fact saved the Russian Revolution, but also saved the honour of international socialism.“

The same can be repeated of Trotsky’s long struggle for a way back to the lost workers’ democracy in the Stalinist states, as well as his analyses of imperialism and fascism and the struggle for a new international and to re-tie the red thread of revolutionary Marxism.